In their latest friendly games against Mexico and Costa Rica, the U.S. women’s national team faced defensive opposition. On both occasions, for different reasons, we saw them struggle to break their opponent down. They beat Mexico 1-0 and drew 0-0 with Costa Rica.

Factors like the heat and the pitch quality no doubt played a part, but this isn’t the first time the U.S. has encountered difficulty turning dominance of both ball and territory into convincing victory. Why? I present a couple of theories in this post. And another theory: that it doesn’t matter much anyway.

Low blocks: who needs them?

Against Mexico, the USWNT enjoyed 71% ball possession. Against Costa Rica, they gained a whopping 80%. These are the kinds of numbers that make victory almost inevitable. Right? Wrong.

Few teams actually relish playing against a low block. The whole idea is to make the game unenjoyable, a slog. Still, the U.S. has more than enough talent to win these games against inferior, defensive opposition fairly straightforwardly. And yet they often don’t.

Those kinds of possession shares are extremely rare in the NWSL, where the vast majority of American internationals ply their trade. It’s a league designed for competitiveness, where the last-placed team one year could win the Championship the next. Low blocks are not really the done thing.

One theory I have is that, perhaps because of this competition, American players don’t get much experience breaking down a low block. It’s not something they see every week, that’s for certain.

Breaking down a low block means attacking in a small space. The distance between and behind lines is minimal. There’s not much room to utilise speed and dribbling skill. It tests the attacking side’s “team play” to the maximum: how well they combine with one another in close proximity, how quickly and accurately they move the ball.

If players aren’t used to this specific attacking challenge at club level, it could be tricky getting them up to speed in short international windows.

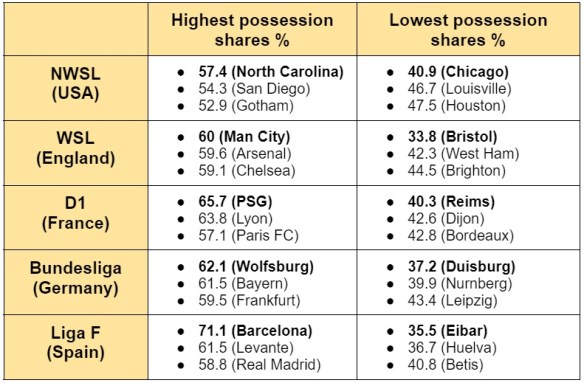

The following numbers back up the idea that the USWNT—many of whom play in the NWSL—are not as used to the low block, and consequent attacking dominance—at club level. These are the three highest and three lowest possession shares in the NWSL compared to Europe’s major leagues.

Data courtesy of FBref. (From the 2024 NWSL season, and 23-24 European season.)

And these are the averages of the top and bottom three possession shares in each league:

Evidently, European teams get more experience of “dominating” their opponent in terms of possession. That doesn’t necessarily mean their national teams are good in this situation, but it can’t hurt.

Maybe this is one of the arguments in favour of American players leaving to experience European football: not that Europe’s top leagues are better, but that their worst teams are worse. Playing inferior opposition more frequently…could somehow benefit the likes of Sophia Smith, Mallory Swanson, Trinity Rodman et al. Really? I don’t know. Maybe it would help them round out their games. Maybe it’s completely irrelevant.

Club continuity, or the lack thereof

When the USWNT gets together, they usually pull players from many different teams. Again, this is a result of the NWSL and its design: very rarely do one or two clubs stockpile all the domestic talent.

This is great for the excitement of the league, but could it be harmful in some small way to the national team? Perhaps, against the low block, it could be.

If we look at the United States’ main rivals at the upcoming Olympics—France, Germany and Spain—we see national teams whose primary sources of talent are a few clubs. Their Olympic squads include players from seven clubs; the U.S. squad includes players from nine clubs.

More drastic are the ‘most represented’ clubs. Spain’s squad includes eight players from Barcelona and five from Real Madrid (72.2% of their squad plays for two clubs). France’s squad includes six players apiece from Lyon and PSG (66.7% of their squad combined). Germany’s squad features six Wolfsburg players and four of Bayern (55.6% of the squad).

The most represented club in the USWNT is Gotham, with six players. After that, it’s several clubs with two players each in the national team.

So what?

Well, attacking a low block requires a synchronicity, a mutual understanding between players. It’s more than passing and moving. It’s speed and timing. This is difficult to develop in short international breaks. Continuity from the club game can help.

Costa Rica (white) defends in a low block v USA. All 10 Costa Rican outfield players are within approx. 30 yards of their own goal. For what it’s worth, six of the 10 play for Saprissa or Alajuelense at club level.

When Spain gets together, Aitana Bonmati, Patri Guijarro, Alexia Putellas, Mariona Caldentey, Salma Paralluelo and Jenni Hermoso understand how to pass and move together from their time together at Barcelona.

Likewise, French attackers like Kadidiatou Diani, Eugenie Le Sommer and Delphine Cascarino know one another well from club play with Lyon. Diani also knows Marie-Antoinette Katoto and Sandy Baltimore from her time with them at PSG.

When the USWNT gets together, those synchronicities from the club level do not exist. Even in the case of Gotham’s six players, three of them—Emily Sonnett, Tierna Davidson and Jenna Nighswonger—play in defence. Crystal Dunn is often used in the back line for the national team, too. That leaves Rose Lavelle, who only recently joined the club, and Lynn Williams.

The pre-existing, unspoken attacking connection apparent in other national teams isn’t such a possibility for the U.S. Maybe that slows them down when they are trying to figure their way through or around a low block? Again, it’s just another idea.

Why all of this could be irrelevant at the Olympics

Having trouble dominating defensive opponents is not the worst problem to have. After the opening stages, games tend to become more even and competitive. There is usually more chance of getting to counter-attack against more willing protagonists. All the U.S. needs to do consistently is bludgeon their way through the group stage and things should become naturally easier.

At this year’s Olympic tournament, the USWNT will face Australia, Germany and Zambia in the group stage. Germany are typically an attacking team, and they have some defensive frailties. Australia are more at home counter-attacking, but aren’t the type of team to sit deep in their own half for prolonged spells. Zambia may be more defensive, and also have Barbra Banda up front to counter with, but should again have enough frailties in the back line for the U.S. to out-score them.

If the U.S. can do enough to finish inside the top two in Group B, as winners or runners-up, they would go into the bottom half of the knockout draw. That would mean avoiding the winners of Group A and Group C—likely hosts France and world champions Spain, respectively. Combining their quality with sheer logistics, the U.S. should have enough to win a medal, at the very least.

Regardless of all the permutations, the point is that the USWNT are unlikely to face a low block of the quality of Costa Rica or Mexico in the group, and perhaps not at all. There should be more openings to play a counter-attacking game, to exploit the speed and skill of their attacking individuals.

That’s the theory, anyway.

Discover more from Women's Soccer Report

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.