In this in-depth analysis, I will go into the United States women’s national team: their style of play, tactics and selections; what’s working and what isn’t; and how head coach Vlatko Andonovski might try to fix remaining issues ahead of the 2023 World Cup.

This initially appeared on The Equalizer. For the latest insights on the USWNT, the NWSL, and women’s football more generally, I highly recommend subscribing to the site.

I wanted to cover the team in as much detail as possible. In case you want to read something specific, here are the contents of this article:

- Part 1: Defensive personnel and the double pivot

- Part 2: Pressing organisation and intensity

- Part 3: Controlling games and counter-attacking

- Part 4: Possession and the narrow front three

Part 1: Defensive personnel and the double pivot

The United States Women’s National Team finished 2022 with a win, beating Germany 2-1 in an entertaining, end-to-end friendly. That victory was crucial for confidence more than anything else, preventing the nightmare of an historic four-game losing streak from becoming reality.

Crises are an important phase in tournament preparation. Almost all national teams go through them, with underwhelming performances and/or poor results fostering negativity about the team’s future. The USWNT has experienced the crisis phase time after time, even on their way to consecutive World Cup wins in 2015 and 2019, so the fears surrounding recent friendly displays are nothing new. In part one I look at the major concerns relating to defensive setup and personnel.

Back four or five?

Normally, teams go to a back five to provide extra security. This could be defensive: hiding vulnerabilities or uncertainty at the back by sharing the same responsibilities among a greater number of players. An example of that could be found at the Houston Dash in May 2022 when, during her interim spell, Sarah Lowden galvanised the team’s fortunes by moving them to a back five, quickly securing a succession of clean sheets.

The back five can also provide offensive security, aiding ball retention by increasing the numbers in the first line of build-up that the opponent must close down, and increasing the back-pass options available to a midfielder under pressure. An example of this was found in Chicago this year, where the Red Stars went from being the team with the lowest average possession share in the NWSL in 2021 to the third-highest in 2022 despite going from a back four to a back five.

Rarely do teams move from back four to back five when everything is going swimmingly, although there are coaches who align to it: Olli Harder is an example in the women’s game, having used this defensive setup during successful spells with Klepp IL and SK Brann Kvinner in Norway, and West Ham United in England. Vlatko Andonovski is not one of those coaches, however. He is adaptable, and would only implement a back five if it was necessary.

After three years on the job without a back five in sight, it’s highly unlikely that Andonovski will introduce it the year of a World Cup. And despite growing concerns over the USWNT’s central defence of late, he doesn’t need to, either.

Alana Cook and Naomi Girma are the two up-and-comers to have forced their way into the conversation around potential starters at next year’s World Cup. They are both athletic centre-backs more than capable of covering the channels on their own. Girma is quick and reads play well—she’s rarely caught out of position, marks up, and is a solid 1-versus-1 defender. Cook has had her issues 1-v-1, but then so has World Cup winner Abby Dahlkemper.

Both Cook and Girma can play out effectively. Cook is one of the best passers in the current centre-back crop, able to play long accurately or feed the next line with an assured, properly weighted pass. Girma is happy to take space when it is given, driving out of defence, and can start the attack with either foot.

As for Dahlkemper’s 2019 partner Becky Sauerbrunn, she remains an important member of the defensive unit at 37 years old. Any drop-off in speed is difficult to discern, and few anticipate danger as well as she does. She defends in a back four for the Portland Thorns, barely getting out of breath in the team’s recent NWSL Championship win, and she hasn’t looked out of place defending in one for the national team. Her experience as the sole remaining starter from the 2019 World Cup-winning back four is invaluable too: she is someone the younger defenders can look to for advice and confidence in times of instability.

Considering the defensive and offensive qualities of these three centre-backs, there is no more need for the USA to abandon its traditional back four than there was in previous years. Andonovski does need to think about depth, though, having only called up three centre-backs for recent friendlies. A lot is riding on the full return to fitness and form of Tierna Davidson, while consistent performers at club level have been ignored (Sam Hiatt, Katie Naughton and Zoe Morse among them).

Nonetheless, where recent games are concerned, any issues with the performances of the centre-backs are less likely to stem from individual shortcomings and more likely down to them being exposed more than before. That is due to difficulties elsewhere on the team, whether that be changes in personnel, team tactics, or some combination of those two factors.

The Ertz Void

Under Andonovski and throughout most of its history, the USWNT has defended in some variation of a 4-3-3 or 4-4-2 system. Within these systems, the defensive midfielder has played a key role in protecting the back line: tracking runs, closing down threats and winning duels to ensure the central defenders are not consistently being run at, overloaded or drawn out of position. For many years, Julie Ertz performed this role single-handedly and uniquely well.

A converted centre-back, Ertz married good positional sense with an incredible determination entering physical and aerial battles—to her, there was no such thing as an unwinnable ball. She was also a vocal leader, cajoling and organising those around her from her position at the heart of the team.

After a knee injury and having just given birth, Ertz has not played for the national team since the Olympics in August 2021. Her absence has been felt—it’s arguable that, outside of Germany’s Lena Oberdorf, there is no defensive midfield problem-solver of Ertz’s calibre in the world game right now. This partly explains why the USWNT centre-backs have not looked as good of late: their workload has gone up and they are being put into difficult situations more often, without Ertz screening the space in front of them.

Here we see a few examples from the October friendly of the US midfield failing to stop England’s attacking players from getting on the ball, playing forward or running at the back line.

Andi Sullivan imposed herself upon the German midfield in the most recent of the two-game friendly series. She brings strength and aggression to 1-v-1 duels, but has yet to demonstrate the nose for danger and mobility of Ertz. Lindsey Horan has been trialled at the base of midfield, but is much more commanding when applying front-foot pressure than when opponents are running at her or past her; she is highly durable, but lacks speed off the mark and the anticipation to make up for that with proactive defensive positioning. More recently, Sam Coffey has been brought into the fold, albeit with limited minutes to show her true capability. Still, she is more creator than destroyer.

Every player has their strengths and weaknesses in a given role, and the USWNT has to accept there is no single player perfectly suited to filling the Ertz void at this precise moment. It’s unwise to assume Ertz will be back and ready to perform in the World Cup, so alternative arrangements should be made, especially considering that Sam Mewis—probably the next-best midfielder when it came to winning duels—has been out for over a year.

Spain’s switch-up and the double pivot

An urgent reminder of the need to re-evaluate the USWNT’s base midfield profiles came in the 2-0 loss away to Spain in October. In that game, Spain switched things up, at times veering away from their customary short-passing game and going long from the back. Consistently throughout that match, the US failed to dominate the aerial duels and lost the subsequent battle for second balls.

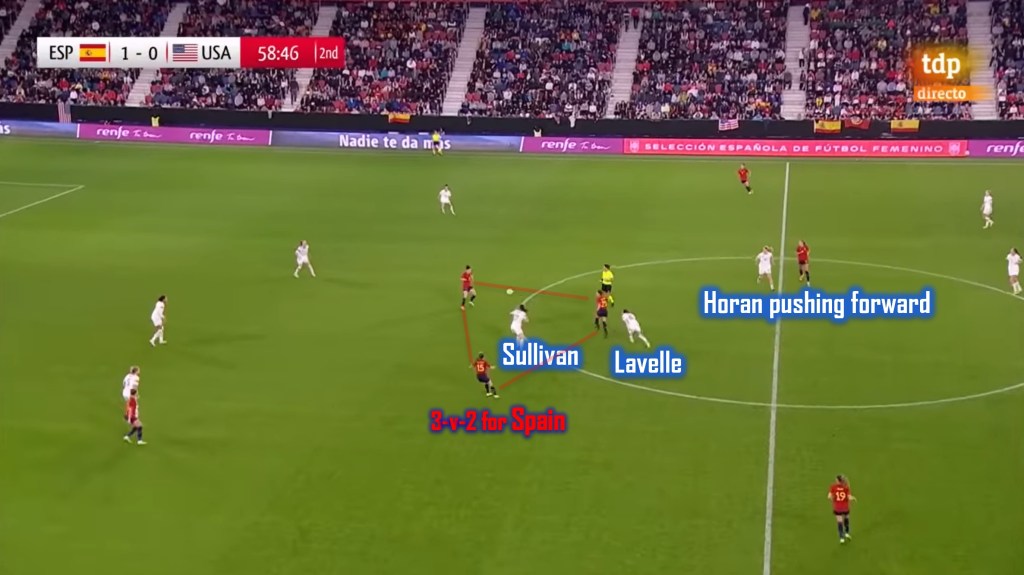

The breakdown at 58 minutes and 45 seconds was an example: Horan gambled on her defensive position, looking to push forward. This left Sullivan and Rose Lavelle in a 2-v-3 situation after the long ball. Spain picked up the second ball, then ran directly at the US back line. Sullivan scrambled to avert the initial danger, but Spain maintained possession and the US were out of shape.

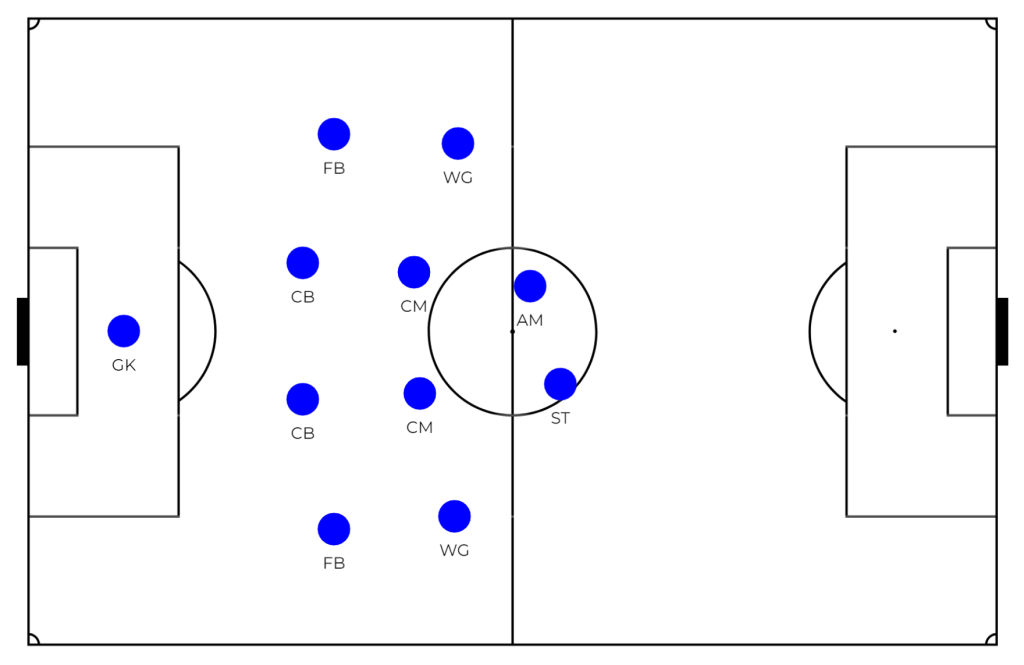

Through his selections, Andonovski has made clear his preference for a midfield featuring Sullivan, Horan and Rose Lavelle. Defensively, the team currently shapes up in a 4-4-2 that almost becomes more of a 4-2-4 when they press. Lavelle moves up to help the striker and wingers close down the opponent’s centre-backs. This puts enormous responsibility on the double pivot to be in-position, working together and ready to deal with threats between the lines.

Horan is an attack-minded player in almost everything that she does, so isn’t always on-hand to work in tandem with Sullivan. In this system, her desire to press forward can sometimes leave her midfield partner with too much ground to cover on her own. If anything, Horan is more suited to a solo shielding role than a double pivot, where the defensive midfield duties are divided and she perhaps feels a greater sense of freedom to roam.

The USWNT has used a double pivot successfully before. In 2015, Jill Ellis lined her World Cup-winning team up in a 4-4-2, with Morgan Gautrat and Lauren Holiday sitting in front of the defence, allowing Carli Lloyd to play a less restrictive role off of Alex Morgan. In that system, Horan would appear much more suited to the Lloyd role—crashing the penalty box, threatening in the air, connecting the attack, operating with a greater range of movement—as opposed to the more rigid, positional Gautrat/Holiday roles.

Every head coach has to look at what their players are realistically capable of and put them in positions to perform their best. At present, Andonovski’s preference to play Horan in a double pivot is not getting the best from her, nor Sullivan, nor the centre-backs. It may be worth looking at more naturally defensive options to help shield the back line (Jaelin Howell, Alex Loera and Olivia van der Jagt have all made good arguments for inclusion).

It makes sense for the USWNT to reconsider their double pivot. Then again, changing the midfield arrangement is merely papering over the cracks if the team’s overall defensive approach doesn’t work.

Part 2: Pressing organisation and intensity

In part two, we will look at how the USWNT defends from the front, knock-on effects on the rest of the team, and what can be improved.

The defence: from 2015 to 2019

In 2015 and 2019, the USWNT won World Cups with very different defensive styles. The 2015 side was to some extent a continuation of Pia Sundhage’s work, with Jill Ellis maintaining the 4-4-2 mid block. That meant the U.S. only started pressing around the halfway line. Two holding midfielders—Morgan Gautrat and Lauren Holiday—protected the centre-backs, while the wingers put in a real defensive effort to track back and help the fullbacks.

2019 saw a shift away from the 4-4-2. Ellis—taking inspiration from Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool team—implemented a 4-3-3 with a narrow front three, in which:

- The striker, Alex Morgan, dropped back to mark the opponent’s base midfielder

- The wingers were in position to close down centre-backs from the outside when the opportunity was there

- There was more emphasis than before on pressing high and nullifying build-up through the middle

- If the opponent found space wide, an energetic midfield trio of Rose Lavelle–Julie Ertz–Sam Mewis shifted to apply pressure on the touchline

Here is a basic overview of what it looked like:

The defence: from Jill to Vlatko

“We’ve gotta stick to who we are. We’ve gotta be aggressive, we’ve got to be intense. We cannot allow [the opponent] to dictate the pace of the game, the tempo of the game. We’ve got to defend on our front foot.“

Vlatko Andonovski, speaking before the USA’s Bronze Medal game at the Tokyo Olympics

Vlatko Andonovski took over from Ellis in October 2019, months after a second straight World Cup win. Initially, he appeared intent on continuing the defensive style seen towards the end of Ellis’ tenure at the very least, if not upping the ante.

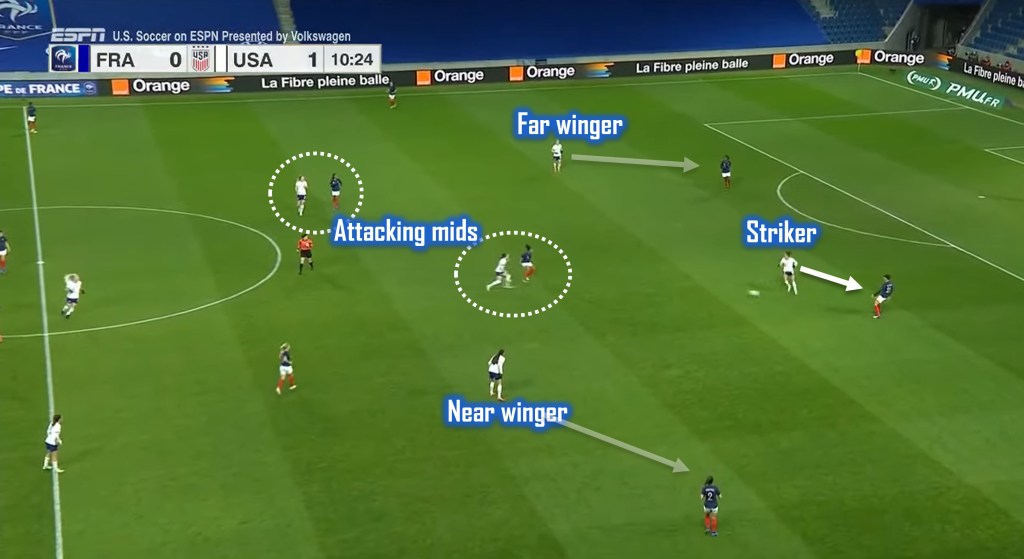

He made small but important changes, opting for a defensive 4-1-4-1, in which:

- The striker would now split the opponent’s centre-backs, steering them to one side of the field (something Carli Lloyd did a fantastic job of)

- This took time away from the opponent and made their build-up more predictable, enabling greater commitment to pressing from the next line

- The far-side winger took the other centre-back, the midfielders marked up, and the nearest winger stayed narrow to force play wide, before closing down that fullback

Here’s how it looked in the friendly win over France (April 2021):

Andonovski put more focus on pressing high and refusing to let opponents cross the halfway line with the ball on the deck. Early on, this approach worked well, and the USWNT were pressing as intensely and effectively as they had done in a long time. Then, there was a disappointing Olympics in 2021, a change of formation, a noticeable drop-off in intensity, and a decline in the team’s defensive fortunes.

Pressing problems in the 4-2-4

After a humbling 3-0 defeat to Sweden in their Olympic opener in Tokyo, Andonovski began to veer away from the confident, aggressive defensive style he initially sought to implement. In the group stage finale 0-0 with Australia, moving to a 4-4-2 shape, the USWNT emphasised containment over pressure.

Post-Olympics, this 4-4-2 became Andonovski’s preferred defensive system. The change occurred without much fanfare, and there weren’t many chances to test it out in the ensuing 12 months. Friendlies against lower-ranked teams such as Uzbekistan, Colombia and Paraguay—among others—provided an opportunity to work on attacking ideas, but not so much defensive solidity. That came to a head in the recent run of friendlies against England, Spain and Germany x2, in which the USWNT failed to keep a clean sheet, conceding seven goals in four games.

Why did Andonovski change his defensive system? Well, it’s unlikely to be coincidence that the change came after a disappointing Olympics, particularly that jarring Sweden loss. And it’s impossible to ignore the prolonged absence of key ball-winners Julie Ertz and Sam Mewis. The theory might have been that fielding two holding midfielders instead of one would fill that void. That hasn’t happened, largely due to a decline in effectiveness and intensity of pressing.

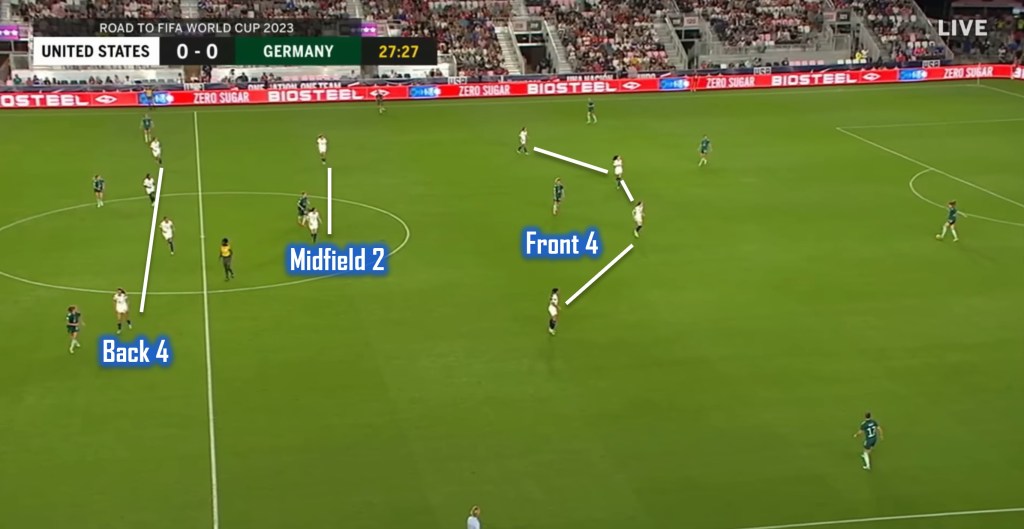

The high pressure that defined the beginning of Andonovski’s spell, where the striker split the centre-backs, took their time away and cut the field in half, is no longer there. Recently, the opposition have enjoyed more time to look up, organise their build-up and pick their passes. This issue is compounded by a lack of compactness in the front four.

What started as a 4-4-2 increasingly looks like a 4-2-4, where the wingers and Lavelle operate on the same line as the striker. When the opponent is able to break through gaps in that first line, a huge burden falls onto just two midfielders—Andi Sullivan and Lindsey Horan—to shut down options and prevent the back line from being exposed.

Right now, the defence appears caught between pressing the ball and staying compact, and isn’t really achieving either of these defensive principles.

It’s possible to succeed while giving the opponent time to play out, as the USWNT did in 2015, so long as the defensive block is compact. It’s also possible to succeed while allowing space between and behind, so long as pressure prevents opponents from accessing that space. EURO 2022 finalists Germany are a good example here. Ideally, the top teams—think Sweden under Peter Gerhardsson or Sarina Wiegman’s England—are able to do both. But it is all but impossible to succeed while giving the opponent time to play out and space to play into.

In the second friendly versus Germany, there were positive signs. Morgan and Lavelle worked as a unit to block routes into midfield while closing down the centre-backs, forcing the opponent outside and into pressure from the USWNT’s wingers. Simply put, the frontline was more compact and applied more pressure, giving Horan and Sullivan an easier job in midfield.

Andonovski may be hoping to perfect this defensive system in the extended preparation pre-World Cup—when his players will be fresher, not at the end of a long club season as they are right now—but it does rely on effective, high pressure. Without that, good passing teams like England, Spain, Germany, France and so on will probably be able to find space between or outside. It’s also trickier to defend at a constant high level of intensity when the games are coming thick and fast, like in the knockout rounds of a major tournament.

With that in mind, here are some realistic defensive scenarios for the USWNT come the 2023 World Cup:

Scenario 1: Pressing high in moments

This could include starting fast like Ellis’ side did consistently in 2019, asking serious questions of the opponent in the first 10-15 minutes, forcing them back and maybe even nabbing a goal, before settling into a lower block that isn’t quite so physically demanding, and only pressing high on obvious triggers or goal kicks.

This would allow Andonovski to retain the current system, but it would also require the players to be absolutely clear on when to press and when to stay in position, and being well-drilled in a mid block to deny passes through the lines. An organised block hasn’t been seen for a while, but could be solved with more international experience for new players and extended prep time pre-tournament.

Scenario 2: Changing the defensive shape

This may involve reintroducing the 4-1-4-1 Andonovski used early on in his tenure. It would ask more of the striker, closing down the opponent’s centre-backs solo, but it would also ensure greater coverage in midfield: no more Sullivan and Horan alone on an island.

Changing system might make it easier to apply effective high pressure. Certainly the team has historically looked more comfortable pressing in some form of a 4-3-3, whether under Andonovski or Ellis beforehand. Few top national teams use a diamond or box midfield. Generally, the max amount of central midfielders used is three, sometimes two. 4-3-3 ensures that the U.S. always has numerical equality in the middle, maybe even one spare to sweep up.

Scenario 3: Changing personnel to mitigate risks

This could involve introducing a striker or a winger, or multiple attackers, that are willing and able to apply themselves not only to high pressure for 90 minutes, but to tracking back to help the midfielders whenever the press is broken. In the 4-4-2 Ellis used in 2015, Tobin Heath and Megan Rapinoe both got back to help protect the fullbacks. At times, Kelley O’Hara was utilised as a defensive winger of sorts, offering the stamina, work rate and quality to support both defence and attack.

This scenario would be the biggest challenge of all, but not from a purely tactical point of view. Andonovski sets his team up by picking the best players and asking everyone to sacrifice defensively. Leaving out one or two of the more talented individuals and introducing more ‘system players’ might improve the defensive balance, but it would also introduce the challenge of keeping top players happy and motivated when they are not always playing.

Andonovski has utilised Lynn Williams as a winger focused on the defensive side, with her speed and work ethic to close down and track back. Ashley Hatch would be another option, to steer the team’s pressing with her athleticism and hunger to shut down centre-backs. The first thing she did after coming on at half-time versus Spain was throw herself at a pass out from the back.

These are the sort of players who can make things easier for those around them, set the tempo from the front, and could enable the team to rediscover the high-pressure defence Andonovski started out trying to implement.

“As a unit, we have to be just a little bit more intense when we’re shifting or closing down opponents. But once again, some of those things we have to work on and get better during training, but some of those things may change or get better just by changing of personnel.“

Vlatko Andonovski, speaking after the defeat to Spain

Many of the USWNT’s greatest successes have been built on effective pressing and organised defence, and there are times during Andonovski’s tenure where this has been a strong point. Since the Olympics and change of formation, however, issues with the team’s intensity and compactness have come to light. The U.S. always has a counter-attacking threat, with outstanding attacking individuals, but doesn’t always have a platform solid enough to generate those opportunities. Over the next few months, rectifying this will be a priority for Andonovski and his staff.

Part 3: Controlling games and counter-attacking

Here, in part three, we will look at how they can control games and provide a threat on the break.

Control without the ball

“We’re going to be defensively organised so that our front players can attack. My philosophy is attacking football, but I believe that your attackers can only have the freedom to do that if you have really strong foundations.“

Casey Stoney, speaking to Attacking Third

It’s a mistake in football to confuse ‘control’ with possession. Teams can control games with the ball, or they can control games without the ball. There is no right or wrong way—it’s a matter of personal choice on behalf of the coaching staff, aligning with the suitability of the players available. Casey Stoney has shown that a team can attack well from a solid defensive base. Only four NWSL teams scored more than her San Diego Wave in 2022 as they made the playoffs in their inaugural season.

Dominating possession or not, the end goal is generally the same: creating and exploiting space in the opponent’s structure. Historically, the USWNT has been more a defend-and-counter team, one that can control the game through defence and generate opportunities in transition, coming from the opponent’s build-up. In 1991, the U.S. won the inaugural World Cup on the back of their pressing and counter-attacking. They tore a possession-based Germany side to shreds in the semi-final.

Layers have been added in recent decades, and rightly so, but counter-attacking remains one of the national team’s biggest strengths. Continuing with that emphasis would be understandable considering the characteristics of the current attacking crop.

Pass and move…or not?

The USWNT incorporates combination play, and has done for some time. In the 2015 FIFA World Cup, Jill Ellis set her team up in a 4-4-2 which saw the wingers—particularly Tobin Heath—free to drift inside and play beneath the strikers, receiving lay-offs from Carli Lloyd.

Clearly, building up the attack from the back is something the USWNT can do, and has done in the past. But this involves a specific type of combination play, one with minimal passes, where the focus is still on getting forward quickly, in that classic U.S. way. The sort of play which is increasingly popular now, implemented at international level by Japan and Spain, is not something the U.S. is used to, nor necessarily best-suited to.

This form of constant pass-and-move play is resolutely committed to controlling the game with the ball, keeping it on the ground and un-balancing the opponent. It is a team game which requires technical proficiency from goalkeeper to striker. To an extent, it also requires that individual players subordinate themselves to the system. That means less freedom of movement—players must work close together to enable short passing. It also means certain restrictions on the ball—players must release the pass within a few touches to keep the move flowing.

At club level, many of the USWNT’s key attackers have great creative licence. With the OL Reign, Rose Lavelle moves freely, which makes sense considering she could find space in a phone booth. The Chicago Red Stars are a possession-based team, but Mallory Pugh single-handedly and successfully injects pace into their play with her 1-v-1 ability. Sophia Smith is now the centrepiece of the Portland Thorns front line, empowered to run the attack and shoot on sight.

“With Soph, you just let her play on instincts.”

Former Portland head coach Rhian Wilkinson, talking about Smith last August

These attackers are not used to playing lots of blurring combinations in close proximity with teammates, and subordinating themselves to the collective attacking system. These are players used to playing with high levels of freedom and individuality, on and off the ball. And these are players who—generally speaking—utilise that freedom well, changing games with their skill and speed.

Of course, developing synergies is crucial, and Vlatko Andonovski will want his attackers to be on the same wavelength come next year’s World Cup. However, it’s challenging for a national team coach to implement something that isn’t widespread at domestic club level. Andonovski has tried to add complexity to the U.S. possession, with more rotations, but results have been mixed.

If, by the summer of 2023, the USWNT can’t consistently free up their most talented attacking individuals to run at opponents via controlled possession and combinations, they should consider doing so by another method: the counter-attack.

Counter-attacking

The USWNT has benefited from a non-stop conveyor belt of 1-v-1 specialists, from Carin ‘Crazy Legs’ Jennings in the early 1990s, through Tobin Heath and Megan Rapinoe, right up to the present day up-and-comers: Pugh, Lavelle, Smith, Rodman. Historically, the U.S. tended to get these players into good attacking situations through its defence and pressing. As opposed to a systematised possession game, they would adopt a systematised defensive game, designed to win the ball and break out before the opponent could reorganise.

Under Andonovski, after three years in charge trying to subtly alter the possession game, the team still looks at its most devastating on the counter-attack. The question then is: how should the USWNT set up to maximise this weapon at the World Cup?

Successful counter-attacking teams are first and foremost good defensive teams. They win the ball off their opponent, then attack the space available in transition. Step one is winning the ball. In recent friendlies against England, Spain and Germany, the U.S. were not compact enough to—as Casey Stoney’s San Diego did this year—control the game without the ball. Gaps in Andonovski’s 4-2-4 defensive system meant the opponent could play through the lines, or come inside via the space outside. Too often, rather than winning the ball, the U.S. were chasing back towards their own goal.

Andonovski will want to develop a better platform from which to generate counter-attacks. That will involve building a more close-knit system, one that can effectively steer the opponent sideways, or into traps. While high pressing is the order of the day, starting in a mid block makes the most sense, and not purely for defensive reasons.

Deploying a mid block, rather than high pressing, means winning the ball further away from goal. This may seem counterintuitive at first, but makes sense considering the profile of the USWNT attackers. With the likes of Smith and Pugh up front, it’s rational to allow the opponent to develop its build-up and become more expansive. This only opens up bigger spaces in their structure. And the more space in transition, the more opportunity for Smith, Pugh et al to generate momentum in foot races and 1-v-1s they are almost certain to win.

From that basic premise of winning the ball around halfway, there are different ideas that Andonovski could try to free up his most dangerous 1-v-1 attackers on the counter-attack. At present, within his preferred 4-2-4, the wide players are liable to get dragged back defensively if the press doesn’t succeed. Counterproductively, that means the likes of Smith and Pugh defending on the edge of their own box, about as far away from goal as it’s possible to be.

A simple solution to this would be bringing in a system player, someone perhaps lacking the dribbling and finishing qualities of the others, but quick, fit, and willing to put in a real shift to help the defence. This could look like the World Cup-winning French men’s team of 2018. Their head coach, Didier Deschamps, balanced out lighting-quick attacking sensation Kylian Mbappe on the right wing with Blaise Matuidi on the left—Matuidi was not only extremely fast and durable, but an intelligent team player with an enormous defensive appetite.

With Matuidi working hard to protect the left-back, close space and work alongside N’Golo Kante and Paul Pogba in midfield, Mbappe could gamble on his defensive position, staying higher to attack space in transition. By having one wide player take on more defensive responsibility, the other could be freed up on the counter. Andonovski would just need to find someone for the defensive job—a 2015 Kelley O’Hara type. Kristie Mewis and Crystal Dunn are players who tick the boxes: quick, technical and hard-working, with experience playing more box-to-box midfield roles.

Alternatively, Andonovski might look to the last USWNT World Cup winners of 2019 for inspiration. Jill Ellis usually set that team up to press from a narrow 4-3-3. The wingers were responsible for closing down centre backs from outside, while striker Alex Morgan dropped back to help cover the opponent’s base midfielders. Perhaps Morgan could do the same job in 2023? That could enable both Smith and Pugh to stay higher and attack space in the channels on the break (like Heath and Rapinoe below). Of course, in 2019 Ellis also had an incredibly athletic midfield three of Lavelle—Julie Ertz—Sam Mewis. The latter two of that three are currently unavailable, so Andonovski would need to make sure his chosen midfield could cover the width of the pitch.

The USWNT can call upon an array of extremely gifted 1-v-1 attackers. They don’t require a complicated possession game to free them up; an organised defensive game can create counter-attacking opportunities in which Smith, Pugh, Lavelle and Rodman can thrive. Of course, that doesn’t mean the team’s possession game should be neglected. Andonovski has a history of building multi-faceted teams, and he’ll want his U.S. side to be the same come 2023.

Part 4: Possession and the narrow front three

In part four, we will look at the team’s possession game: what Andonovski has tried to add and where it can develop.

Patterns from the past

The history of the USWNT possession game has some recurring themes. One is skipping the midfield in build-up, playing straight into the frontline, with a ball along the ground or in the air towards a focal point combining good control with strength and aerial power (Michelle Akers, Abby Wambach, Carli Lloyd) or quickly feeding a fast, tricky winger as quickly as possible to get them 1-v-1. Another theme is the fullbacks playing a more supportive role. Rarely getting beyond the frontline, they have traditionally been tasked with initiating build-up and ensuring a stable base in case of turnovers.

More complexity has come into the team’s possession in recent times, particularly under Jill Ellis. At the 2015 World Cup there was a 4-4-2 where the wingers regularly drifted inside and Lloyd played slightly off of Alex Morgan up front, providing options to hit between the lines. The 2016 Olympic quarter final defeat to Sweden saw probably the most complex attacking setup seen in national team history: an asymmetrical system where one fullback stayed deep and the other pushed up; and one winger stayed wide and the other came infield.

That system didn’t really work—lacking dynamism on the left, it was too predictable and Pia Sundhage’s total defence, low block 4-5-1 Sweden team ground out a victory. After that, there was more experimentation before Ellis got back to basics in the 2019 World Cup. There were wingers that stretched the field, receiving diagonals from the back (see: Dahlkemper’s ball to Christen Press below) and running at their opponents. Sometimes the attacking midfielders would pull wide to work with the fullbacks, overloading the opponent on the flanks.

Ultimately, a lot of the 2019 team’s best play came down the wings, with a focus on working quality crosses. At the end of that tournament, according to FIFA’s technical report, the United States were eighth of 32 teams for average ball possession, but top for cross success percentage with 29 percent—nine percent above the tournament average. Considering the quality of the team’s wing play, service from the likes of Rapinoe, and with a finisher like Alex Morgan and aerial threats like Sam Mewis, Horan, occasionally Ertz crashing the box, those numbers weren’t surprising.

Ellis successfully embedded new ideas within the team’s possession, though the main premise remained the same as it always has been: go from building to attacking as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Vlatko-ball: the idea

Andonovski arrived in late 2019 with the intention of building on the groundwork laid down before him. He clearly attempted to instil greater emphasis on keeping the ball on the ground, and playing through the lines rather than over the top or around the outside. His major tactical change was implementing a narrow front three. Instead of wingers opening up the field for diagonals, as they had done at the 2019 World Cup, the front three played inside of the opponent’s defence.

The basic theory with the narrow front three appeared to be adding extra options between the lines—one of three forwards could receive the ball to feet and link play. Alternatively, with one forward withdrawing and others threatening in behind, the opponent’s defence could be confused, and space could be created. These movements have rarely had chance to work, however, mainly because:

- Many opponents the U.S. played in recent years defended in a low block. They had no interest in following the striker dropping deep, and took away the space behind (think South Korea, Czech Republic).

- There were games—like the Concacaf final versus Canada—where the U.S. couldn’t enact these movements because they weren’t dominating possession and were more focused on counter-attacking.

The idea of adding layers to the team’s game was fine—and no doubt partly the consequence of fears that traditional methods were becoming outdated, despite another World Cup win as recently as 2019—but the implementation has run into challenges of various kinds.

Challenges and solutions

“Too many errors from us, again. The space was there for us to play in, and we just couldn’t get into it—too many touches or an errant touch.”

Megan Rapinoe, speaking after the USA’s defeat to Canada at the Tokyo Olympics

After a loss to Canada in which the United States enjoyed just under 60 percent possession, the players and head coach were at a loss as to why things hadn’t worked out. They dominated the ball but couldn’t score, and lost to a Jessie Fleming penalty kick. There was no doubt the national team no longer looked itself—the gleam of that 2019 World Cup win had well and truly worn off, a 3-0 loss to Sweden in the Olympic opener proving impossible to recover from.

Against Sweden, the U.S. were counter-attacked into submission; it was essentially a flip reversal of what they had done to so many opponents over the years. Errors in the team’s build-up had been punished and used against them. It was one of the most crushing defeats in program history, and it highlighted issues in possession that they have continued to encounter since. Let’s look at some of those challenges, and potential solutions.

The disconnect

One of the big stumbling blocks undercutting Andonovski’s attempted implementation of more short passing and combinations has been the disconnect between players. Huge distances between the back line and the midfield/front lines have made it almost impossible for the team to combine their way out of pressure. Here’s an example from the Olympic loss to Canada, where there is almost half a field between Becky Saeurbrunn and her forward passing options.

And here’s an example from the first friendly against Germany more recently. Again, there’s a big gap between Sauerbrunn, in possession, and her forward options.

Making passes over these distances allows the opponent more time to get pressure on the ball. It also puts huge onus on the passer to play a perfectly accurate and well-weighted ball, and on the receiver to control that ball instantly and keep it under pressure from an opponent. Playing quick passes or one-twos over these distances is simply not a good idea; even the very best players could lose control of possession in this kind of situation.

There’s a double whammy, too, with such an expansive attacking shape. Here’s what can happen when the receiver doesn’t perfectly control that pass…

The more expansive a team is, the more technically assured, strong and composed each individual player must be, particularly under pressure. Poor first touches and inaccurate, over-hit or under-hit passes not only kill off the build-up (as happened in the Olympics against Canada), but give opportunities for the opponent to counter-attack into those big gaps between players (as happened in the recent friendlies against Germany).

For this World Cup, Andonovski may need to lean heavily on Catarina Macario, assuming she returns to full fitness and form. Few players in the world combine Macario’s close control, trickery and strength to shield the ball—she can keep the ball even in this sort of overly expansive system. That would necessitate playing deeper, however—not as a withdrawing No.9 as Andonovski previously utilised her. With Macario in a midfield role, she can offer an option to the centre-backs, keep it under pressure, and open up defences from deep. She has the quality to quarterback the team’s possession, if given licence to do so.

Greater onus than ever before will also fall on the centre-backs and defensive midfielders, who must be accurate in their long-range passing and capable of taking the ball into midfield if nothing is on. In this sense, the emergence of Naomi Girma is a game-changer: she is comfortable running the ball forward and can pass off either foot. It would be unwise to ignore the passing range of Sam Coffey at the base of midfield, too, to connect with teammates over those long distances.

If—over the next few months—Andonovski is unable to find ways of setting the team up more compactly in attack, it will be difficult to implement any sort of effective short-passing, combination game. He would then need to rely on individuals to execute under pressure.

The lack of width

One of the major problems associated with Andonovski’s narrow attacking front three is the consequent lack of width. The sweeping diagonal ball from centre-back to winger—the sort of pass Dahlkemper provided so well in 2019—is no longer viable. Passes are regularly forced through the middle, simply because there is no alternative.

One problem with this is that it makes the United States’ play more predictable—opponents know to stay compact and get tight to any receivers in the middle, pressure them and try to force turnovers. It also creates danger in transition—it’s easier for an opponent to control and generate momentum on the counter off of a short pass interception through the middle than after a long ball in the air or on the touchline.

There has also been a lack of quality wing play, with all three of the frontline often seen inside the opponent’s defence. When the wingers do receive wide, they are now running from in-to-out, away from goal, usually with a defender tailing them. That makes it harder for the winger to get into full speed running at the defender, reducing their chances of working a dangerous cross, pass or shot.

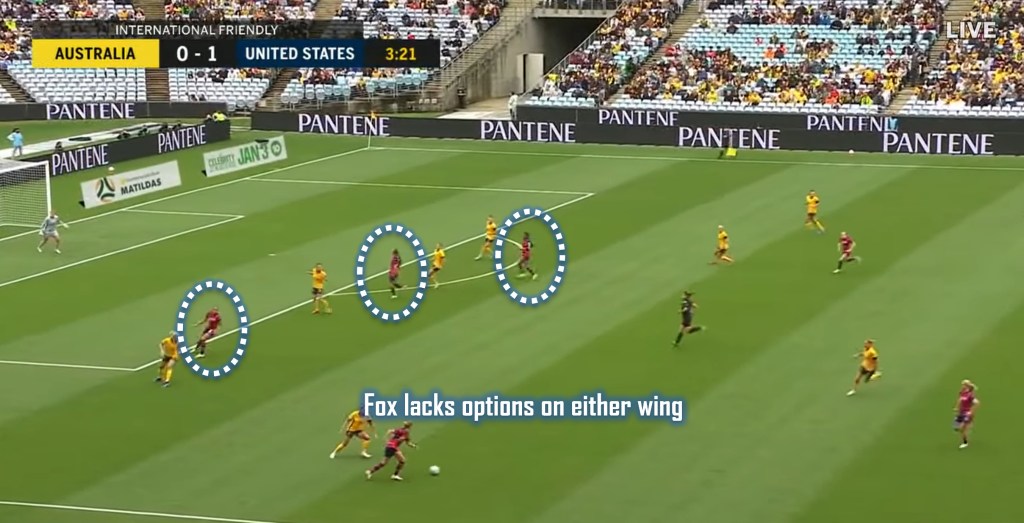

Furthermore, without wingers to combine with, it’s impossible for the fullbacks to work combinations on either flank. Below we see an example from the friendly win over Australia last year. Emily Fox receives on the left flank, but the left winger is inside, not available to combine with. Having then cut back, Fox finds no option for the switch of play, because the right winger is also narrow. There is no width to enable combinations or switches of play.

As a consequence of the lack of width from the forwards, one of the regular patterns seen as a solution is Horan pulling out to wide left. But Horan vacating midfield has a knock-on effect. To avoid only having three players behind the ball to defend a counter (the centre-backs plus Andi Sullivan), the U.S. right-fullback must then stay back. If the right winger is also infield at that moment, there is no opportunity for the quick switch of play.

When opponents congest the centre, as they so often do against the United States, this narrow attacking system puts extra responsibility on the fullbacks to get forward and offer quality service. With someone like Sofia Huerta on the right—a converted winger with a sensational cross—that’s not an issue. But on the left, Emily Fox is more inclined to come infield than overlap. With all of this mind, the lack of game time given to Carson Pickett—a natural overlapping left-footed fullback with a great cross—is puzzling.

There are three possible solutions. One is that Andonovski moves away from the current attacking system, to a more traditional 4-3-3 with more width in the frontline, like Heath and Rapinoe provided in 2019. The second is that the fullback profiles change—and players like Pickett gain more consideration—to ensure overlapping runs and quality crosses. Another option is tactical: developing more dynamism on the flanks, perhaps taking a lead from the French national team, to generate simple one-two combinations between fullback, winger and midfielder.

The USWNT remains one of the most dangerous attacking teams in the world, with an array of brilliant forwards and creative players. On the counterattack, they can still hammer just about any defence. Even though the new ideas Andonovski has sought to implement haven’t quite clicked yet, there is still time to make changes and improvements. This team can go deep in the 2023 World Cup. Preparing to win the competition, however, means issues with the defensive and possession games cannot be ignored.

Discover more from Women's Soccer Report

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.