I decided to look into aerial duel data for two reasons.

One is that I believe 1v1 duels, including aerial duels, are important in football, and are due more serious investigation. Football is a low-scoring sport where clean sheets can be crucial, and the ability to win aerial duels plays a role in keeping clean sheets. Losing an aerial duel can lead to: a shooting opportunity in your box; an opportunity for a striker to run in behind your defense; an opportunity for the opponent to put pressure on you in your own half; a dangerous transitional situation. The aerial duel should not be underestimated.

Two is that I believe that the technique and complexity in aerial duels is being over-simplified in current analysis. There is a lot of interest in set piece routines, and defenders who can score goals from corners, but not so much in 1v1 defending on long balls, high crosses. I also don’t think the data paints a proper picture of aerial duel success.

Hopefully, this article will push the conversation around aerial duels along.

Aerial ability: a skill to evaluate

Let’s start by breaking down what goes into winning an aerial duel. The most obvious aspect is height. Being a foot taller than your direct opponent will be a help. Leap is also important, and can be a big leveler. We can probably all think of players who can/could consistently out-jump opponents several inches taller. Upper body strength is helpful too, when competing 1v1 with an opponent.

Height, leap and strength are physical aspects, and of course there are mental aspects: bravery, commitment, whatever you wish to call it. There are also technical aspects involved in aerial duels. Things like reading the flight of the ball, timing the jump correctly, making good contact, positioning.

“On any long ball, people try to outjump each other. I don’t mind a big jump, but to be honest, the only thing you have to do is fight for the spot where the ball is going to land. If you own that zone, it’s going on your head, and you don’t even need to jump.”

Vincent Kompany, talking to Grant Wahl, in the book Football 2.0

So…height relative to the opponent is important, but it is not the only factor in aerial duel success. Other physical, mental and technical factors are relevant. There is skill involved, and we can evaluate players on their skill level. We can look at data and video to do this.

Different types of aerial duel

Let’s continue by looking at the different types of aerial duel:

- Attacking set piece (corner, free kick, throw-in) or high cross in open play

- Defending set piece (corner, free kick, throw-in) or high cross in open play

- Attacking a long ball

- Defending a long ball

Of course there are other aerial duel situations, but these are the ones we see most consistently in games of football. Each one is pretty unique.

There is an obvious difference in risk with aerial duels when attacking a set piece compared to defending one. When attacking a high cross into the opposition’s box, the player has license to be more aggressive in the knowledge that if they foul or miss, they don’t concede a penalty or a goal. There is also more control at attacking set pieces – teams have routines that are designed to target and/or isolate certain players. By contrast, when defending a high cross into their own box, the defender knows a mistake might result in a penalty, a shot or a goal.

There are also obvious differences in aerial duel situations in open play. Defending a long ball from the opponent’s goalkeeper, for example, gives more time for the defender to prepare and gain momentum going into the challenge. By contrast, when defending a high cross into their own box, the defender not only has less time to prepare, but also with more players nearby they can have a worse view of both the ball and the runs being made all around them. It’s a more complex situation.

It’s pretty clear, at least from where I’m sitting, that winning aerial duels in your own penalty box is different to winning them elsewhere in your own half, or in the opponent’s half, and that defending a set piece is different to attacking one.

So…why on earth would we lump all aerial duels into the same category?

To me, this is no different to judging a player’s passing skill on their pass accuracy percentage. The information may not be completely irrelevant, but it is limited. A player might have high pass accuracy because they only play short or simple passes. Or they might just be exceptionally accurate. We certainly cannot confidently say that those with the highest pass accuracy are the ‘best’ passers!

By the same token, we should not assume players with the highest aerial duel percentage are the best in the air. That those who are good at attacking corner kicks are equally good at defending them. Or that those who win the majority of their aerial duels just past the halfway line are equally effective winning them in their own penalty area.

More nuance in evaluating aerial duel success

The data I have access to is Wyscout and FBref. FBref breaks down aerial duels by ‘Won’ and ‘Lost’, and gives a percentage of aerials won. This is not completely useless, but it’s not something worth paying specific attention to, making recruitment or tactical choices on. Wyscout offers a bit more detail, with the option to break aerial duels down into ‘Total’ and ‘In own penalty area’. But this is still quite limited, and there is another issue in my opinion:

What counts as an aerial duel win?

Does the defender clearly ‘win’ the aerial duel if, after misjudging the ball flight or mistiming their jump, the ball skids off the top of their head and goes behind them, closer to their own goal? In Wyscout’s opinion, yes. In my opinion, no.

Does the defender clearly ‘win’ the aerial duel if, after making contact with the ball, their technique is poor and the ball trajectory is sharply downward into the direct opponent they were trying to beat, or veering off sideways, gaining no ground, and/or creating a potentially dangerous loose ball scenario? In Wyscout’s opinion, yes. In my opinion, no.

Does the defender ‘lose’ an aerial duel if neither they nor their direct opponent makes contact with the ball? In Wyscout’s opinion, yes. I’m not sure, so I’m going with no again.

This is the problem with a simplistic approach to aerial duels. ‘Wins’ can in fact be poor contacts with the ball that create even more problems than if the defender had simply let their opponent have the ball! And if both players miss the ball, neither has won the duel and neither has lost it, but these are counted as ‘Losses’. So both players lost a 1v1 duel…what!?

In my opinion, there needs to be a third column next to Win/Loss. I propose calling this: ‘Neutral’.

Let’s analyse!

After all that, it’s time to put my ideas into action. I want to find out what happens if I evaluate aerial duel success using my Win/Loss/Neutral angle, with ‘Neutral’ being my assessment when an aerial duel is:

- Won by neither competitor in the 1v1 duel

- Won, but not convincingly (ball goes nowhere, or behind, or is completely out of control)

I’m particularly interested in defensive aerial duels, so I will not count attacking situations, set pieces, etc. As discussed above, these are different settings, and other factors come into play such as the quality of delivery from a teammate, the quality of set piece routine, and the simple fact there is more license to be aggressive and make errors.

I watch a lot of the Women’s Super League, so this is where I will focus on. I picked a few central defenders from this league, and looked at their last 50 ‘defensive’ headers. That, I hope/think, should be a decent enough sample size.

For each player, I graded each of their aerial duels as Win, Loss, or Neutral.

I also separated the duels by location on the pitch: 1) in their own box, 2) elsewhere in their own half, and 3) in the opposition’s half.

I also made sure to specifically only count 1v1 defensive aerial duels. I’m not interested in unfair situations where the defender is blocked, out-numbered or sandwiched, or gimmes where the opponent doesn’t even pretend to contest. None of these are 1v1 duels.

The WSL centre-backs I evaluated were: Molly Bartrip, Millie Bright, Magdalena Eriksson, Gemma Evans, Alex Greenwood, Alanna Kennedy, Maria Thorisdottir, Amy Turner, Victoria Williams, and Leah Williamson.

Of course, I did this myself and there were a lot of duels watched and graded. It’s possible that I made errors somewhere along the line, though I like to think this will not make my analysis completely redundant.

Results: Clear Win percentages

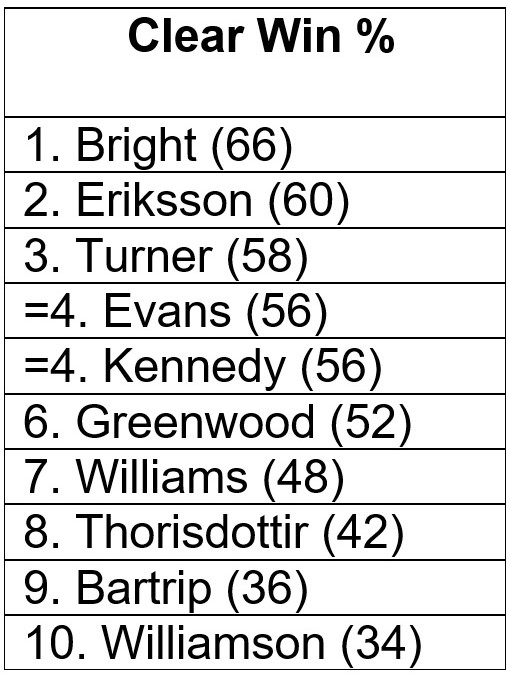

Of the 10 WSL centre-backs I analysed, here is their ranking in percentage of defensive aerial duels they clearly won:

Millie Bright is the standout here, which may not surprise those who just watched her head everything away during England’s run to Euro 2022 success. Her Chelsea teammate Magdalena Eriksson is second, just ahead of Tottenham’s Amy Turner (I counted her 20/21 season data from her time with Manchester United). Then it’s Gemma Evans of Reading, level with Manchester City’s Alanna Kennedy, followed by Alex Greenwood. Leah Williamson and Molly Bartrip are well behind everyone else.

For what it’s worth, here’s how these 10 players fared on my ‘Clear Win’ rankings compared to Wyscout and FBref’s more generic aerial duel success percentages.

A couple of things you may notice from this comparison. 1) Every player is ranked in roughly the same order. 2) Every player’s win percentage gets progressively higher from my method, to Wyscout’s, then to FBref’s (Thorisdottir is the exception – her win percentage goes down from 58.3% per Wyscout to 57.1% per FBref).

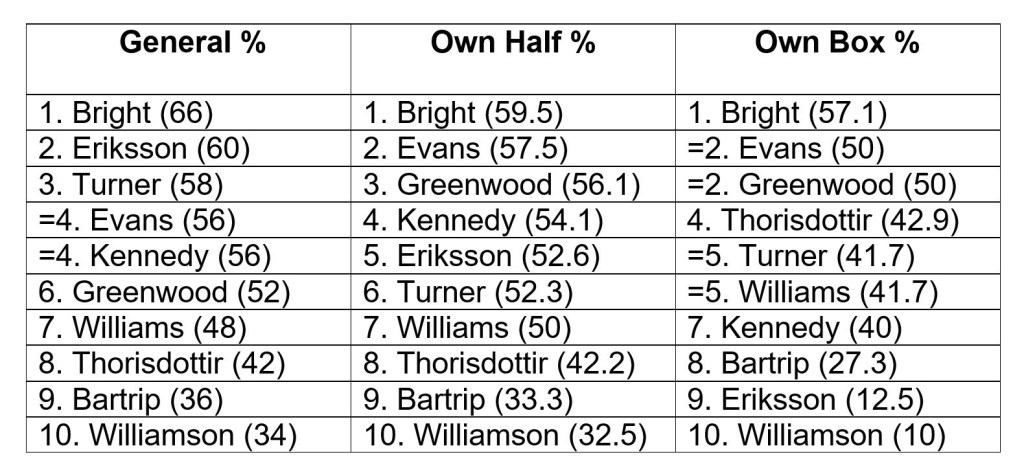

Results: Clear Win percentages by location

You might also remember that earlier in this article I separated out the aerial duels by location on the field. Well, here are the results. Now we can compare how players do in defensive aerial duels generally, to how they do specifically in their own half, and specifically in their own box.

You’ll notice that Millie Bright remains top everywhere, and is clearly the best in 1v1 aerial duels in her own box. Gemma Evans is also near the top of all three rankings, which suggests a consistency, if not the same level of dominance as Bright. At the other end of the scale, Leah Williamson remains consistently at the bottom of the rankings no matter where the aerial duels take place.

Most players’ win percentage got worse the deeper on the field they got, and all bar one experienced a drop off in success in their own box (the exception was Thorisdottir, but that was a barely noticeable 0.7% upturn). This makes sense to me, considering what I said earlier about the increasing complexity of dealing with a high ball into your own box compared to elsewhere in your own half or further up the field. In my mind, defenders should find it harder to clearly win aerial duels in their own box, and the numbers back that up.

There are some peculiarities, though…

Going from ‘own half’ to specifically ‘own box’, the average change in percentage of clear wins is -11.7%. Three players, however, experience declines above that average: Alanna Kennedy, Leah Williamson, and Magdalena Eriksson.

Kennedy and Williamson are former midfielders playing in central defence for their clubs, which might explain why they look significantly less assured dealing with aerial duels in their own box: it’s possibly something as simple as their not being used to or specialists in contesting in that area and all its complexity (with crosses into the box, compared to long balls down the middle, I think it’s fair to say that there is greater variety regarding: ball flight, speed, bend, not to mention less preparation time, and a greater number of players and movements being made in close proximity to the aerial duel).

Williamson won just one of 10 aerial duels in her own box, which is perhaps something Arsenal opponents may wish to take note of when they do their pre-match preparation.

Eriksson is the really peculiar case though: she experiences a 40% drop off from aerial duels in her own half to those specifically in her own box, where her win rate is only slightly higher than Williamson’s. Playing for Chelsea and often as an outside-back in a back three, Eriksson gets lots of aerial duels just inside the opposition half, where she can be a bit more aggressive and may come up against smaller opponents in wider positions. This might explain the discrepancy between her overall clear win percentage, which is good – second only to her teammate Bright’s – and her low percentage in her own box.

But wait – there’s more to take into consideration!

Winning vs. Not Losing

It’s one thing to see how many clear wins a defender obtains in their aerial duels, but that doesn’t necessarily give us the full picture either. When defending in your own half and your own box, it’s arguable that not losing the duel is almost as important as winning it.

I also had the inkling that there are gung-ho centre-backs out there who are boom or bust in these situations: either they win the aerial duel clearly or they lose it. These types of defender offer less consistency and predictability in their performance in aerial duels, which becomes more problematic the closer to goal they defend.

This could be something to watch out for when recruiting. If you’re a low block defensive side, is it better to sign someone who clearly wins 50% of her own penalty box aerial duels but loses the other 50%, or someone who clearly wins 30% but only loses 10%? Possibly the latter?

Either way, it’s of interest, and I wanted to see if the data I collected backed up my idea that some centre-backs in aerial duels are:

- Boom or bust (sometimes win clearly, sometimes lose)

- Competitive, but not dominant (don’t win lots, but also don’t lose many. They do just enough to obstruct the opponent, for example)

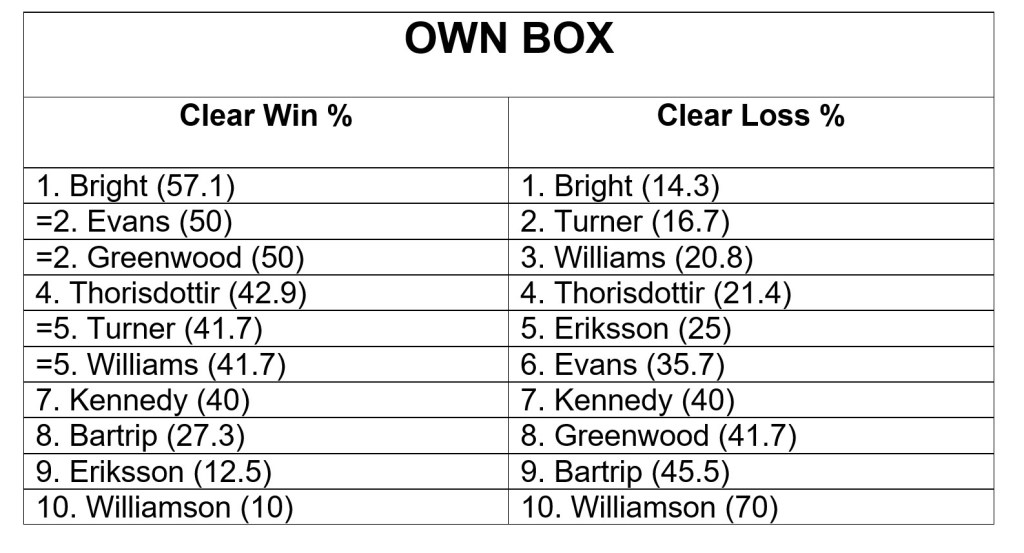

To do this, I need to combine ‘Clear Win’ and ‘Clear Loss’ percentages, based on the aerial duels I looked at.

Here are the Clear Win and Clear Loss rankings for the centre-backs’ aerial duels in their own half overall (including their own box):

And here are the ‘clear win’ and ‘clear loss’ rankings for these 10 centre-backs on aerial duels in their own box:

As you can see, Millie Bright is at the top of all the rankings. She wins more and loses less than anyone else. Again, no real surprises here. (Sidenote: do we still need Bruce Willis to blow up the asteroid when we could just have Millie Bright head away the danger?)

Another player that is near the top of both rankings is Amy Turner. If Bright is ‘dominant’ in aerial duels, we might describe Turner as ‘competitive’.

There’s also consistency with Molly Bartrip and Leah Williamson – both are near or at the bottom of both rankings. We might term these types of players as ‘weak’ in these situations, as opposed to competitive or dominant.

This way of looking at the data offers us another insight into Magdalena Eriksson, too. Yes, in her own penalty box, her win rate does drop off a cliff. BUT she doesn’t lose many of these duels either. Perhaps that win rate isn’t so worrisome with this extra context – she can compete, if not clearly win, on most aerial duels in her box.

The three really interesting cases, from my point of view, are Gemma Evans, Alex Greenwood and Alanna Kennedy. Evans and Greenwood are high up on the Clear Win rankings, but much lower down the Clear Loss rankings, indicating they might be ‘boom or bust’ – if they aren’t winning the duel, they are losing it, and that’s that. In her own box, Kennedy loses just as many as she wins.

Any manager just looking at the Clear Win percentages of Evans and Greenwood, specifically, might be fooled into believing these players are are solid on aerial duels in their own penalty area. They aren’t far off Millie Bright, after all! But if the manager then saw their Clear Loss percentages, where they are closer to Molly Bartrip than to Millie Bright, they would undoubtedly think again.

Limitations of this analysis

I only looked at the last 50 defensive aerial duels for each of these central defenders. A larger sample size would be more robust, particularly when looking at aerial duels in their own box. Of the duels counted for each player, the most that any player had that took place in their own box was 24 – Victoria Williams. Others had far fewer. Of Leah Williamson’s 50 duels, for instance, just 10 were in her own penalty area. While she clearly lost seven of those, which is not a good sign, it is admittedly a small sample size, so we may wish to think twice before buying a one-way ticket for that particular bandwagon.

And there is another factor which can skew the results: tactics!

Some teams defend corners with man-marking, others use zonal marking, and some use a hybrid of the two. These different marking systems impact players in different ways. For example, a quick and agile defender might be difficult to shake off in a man-marking system, whereas a slow one might find it harder to keep up with runners and well-executed corner routines.

In a man-marking approach, the slow defender may not stay with her opponent and lose the duel. However, if she were instead given a zonal marking job in the middle of the six-yard box, like Wendie Renard has at Lyon, with licence to concentrate purely on attacking the high ball, her numbers may look better.

Quick summary

While it has its limitations, I think this study throws up some interesting ideas that may be worth further investigation. Here is a quick summary:

- Aerial duels are not the same all over the pitch, and some players perform differently in different aerial duel situations

- The old Won/Lost method to grading an aerial duel is overly simplistic. Adding a third ‘Neutral’ column offers more clarity

- We might be able to separate centre-backs out into at least four different aerial duel classifications: dominant (win most of the time); competitive (don’t lose most of the time); weak (lose most of the time); and boom/bust (win some, lose some)

Conclusion

All of the information thrown up from this analysis can have implications on recruitment and game management.

If you are, say, Emma Hayes, and you are wanting to build a Chelsea team that presses high up the field, you probably aren’t quite so concerned about a defender’s ability to win aerial duels in their own penalty box. You might look more at the player’s general aerial duel percentage, and throw that in with their speed and other technical characteristics that are important to playing in a high line.

However, if you’re Carla Ward, and you manage an Aston Villa that defends in a low block more often, and you want to build a back line that can deal with high balls into their own box, then you absolutely will be interested in that specific aerial duel data. And if Villa are playing Chelsea, and you know Chelsea can play quite directly, and you know they have Sam Kerr up front, then you maybe pick the centre-back who is most aerially dominant in her own box even if she falls short in other areas when compared to her colleagues.

If the aerial duel is important, and I believe it is, then more nuanced data is needed to reflect all the different locations and situations they take place in, and more clarity is needed as to what exactly constitutes an aerial duel success. Hopefully this analysis has highlighted some of the problems in the current data we see on Wyscout, FBref etc., and hopefully it has also provided new insight on the aerial duel in general.

Thanks for reading!

Blair

Discover more from Women's Soccer Report

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.